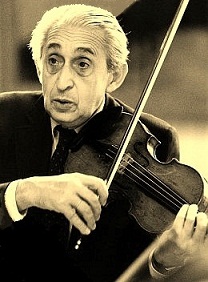

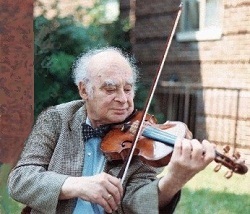

Daniel Guilet (Guilevitch) was a Russian violinist

(some would say French or American) born (in Rostov) on January 10, 1899. Although he was for a few years concertmaster

of the famous NBC Symphony under the ill-tempered Arturo Toscanini, he is

better known as the original violinist and founder of the Beaux Arts Trio. His parents moved from Russia to Paris before

the turn of the century, and he later trained at the Paris Conservatory with

George Enesco. After graduation, he

toured Europe as a recitalist with Maurice Ravel as his accompanist. He also played second violin in the Calvet

String Quartet (with Joseph Calvet, Leon Pascal, and Paul Mas.) A YouTube audio file of one of their

recordings can be found here. Guilet

came to the U.S. in 1941. He was about

41 years old. He soon formed a quartet (which at various times included Henry Siegl,

Jac Godoretzky, William Schoen, Frank Brieff, David Soyer, and Lucien Laporte) under his own name. A YouTube

performance by this quartet can be heard here.

Three years later (1944) he joined the NBC Symphony. Seven years after that (1951), he became its

concertmaster and remained in that position after Toscanini retired in 1954,

although the orchestra had to change its name – a string quartet from the NBC

orchestra which included Emanuel Vardi and Daniel Guilet, used to play for the

retired maestro at his home almost every Sunday in order to cheer him up. In that same year (1954), Guilet formed the

Beaux Arts Trio with pianist Menahem Pressler and cellist Bernard

Greenhouse. The trio gave its first

concert on July 13, 1955 and its last on September 6, 2008. Guilet retired from the trio in 1968 and from

playing altogether (publicly) in 1969. The

trio (featuring Guilet) has a few audio files on YouTube although files and

videos with subsequent violinists are more numerous. One such audio file is here. After his retirement, Guilet taught at

Indiana University, the Manhattan School of Music, the Royal Conservatory in

Canada (Montreal), Oklahoma University, and Baylor University (Waco,

Texas.) He owned a JB Vuillaume violin

from 1867, a Carlo (or Michele Angelo) Bergonzi from 1743, and a 1727

Guarnerius Del Gesu which he got rid of in 1973 (after he retired from playing)

and which passed through the hands – perhaps in 1998 - of infamous violin

dealer Dietmar Machold, who is now in prison for defrauding clients and banks. I’m guessing Guilet used the Vuillaume and Bergonzi

violins for most of his recordings since the Guarnerius was not acquired until

1965. The violin now bears Guilet’s

name. Guilet died in New York on October

14, 1990, in relative obscurity, at age 91.

Friday, December 28, 2012

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Sherlock Holmes quote

“There

is nothing more to be said or to be done tonight, so hand me over my violin and

let us try to forget for half an hour the miserable weather and the still more

miserable ways of our fellowmen.” - Arthur Conan Doyle, quoting Sherlock Holmes

“There

is nothing more to be said or to be done tonight, so hand me over my violin and

let us try to forget for half an hour the miserable weather and the still more

miserable ways of our fellowmen.” - Arthur Conan Doyle, quoting Sherlock Holmes

Holmes was talking about the London weather, which can sometimes be nasty. The quote is from the story entitled The Five Orange Pips. If you have played for some time, you know full well that once you get "into" your playing, you forget pretty nearly every other problem or concern you have - the violin is like a refuge from mundane matters. Perhaps the reason is not a poetic one, but a practical one - it takes a lot of concentration so you are simply not able to focus on anything else with meaningful intensity.

Sunday, December 23, 2012

Robert Schumann quote

“If we were all determined to play the first violin we should never have

an ensemble. Therefore, respect every

musician in his proper place.” Robert

Schumann, pianist-composer

“If we were all determined to play the first violin we should never have

an ensemble. Therefore, respect every

musician in his proper place.” Robert

Schumann, pianist-composer

Schumann had the right idea. Throughout history, the orchestra has supported innumerable musicians of considerable talent. Many orchestral players have gone ahead to forge great music careers after leaving the orchestra. Those players include Israel Baker, Max Bendix, Elias

Breeskin, Pablo Casals, Carmine Coppola, Joseph Joachim, Louis Spohr, Heimo

Haitto, Neville Marriner, Frank Miller, Charles Munch, Eugene Ormandy, Arturo Toscanini, Janos Starker, Roberto Diaz, Mischa Elman, Zino Francescatti,

Leonard Rose, Joseph Fuchs, Milton Katims, William Primrose, Josef Gingold, Daniel

Guilet, Alan Gilbert, Felix Galimir, Orlando Barera, Mischa Mischakoff, Louis

Persinger, Andor Toth, Gerard Schwarz, Oscar Shumsky, Peter Stolyarski, Theodore Thomas, Lynn Harrell, Jaap Van Zweden, Emanuel

Vardi, Tossy Spivakovsky, and Eugene Ysaye. You never know if you'll be sharing a stand with the next Mischa Elman, Alan Gilbert, or Arturo Toscanini.

Saturday, December 22, 2012

Isaac Stern quote

"Outsiders always look for a reason to explain why they are not

inside. They never look in the mirror.

Let's face it, the profession I'm in is a very simple and a very cruel one.

There is no way that you can create a career for someone without talent and no

way to stop a career of someone with talent." - Isaac Stern, violinist

"Outsiders always look for a reason to explain why they are not

inside. They never look in the mirror.

Let's face it, the profession I'm in is a very simple and a very cruel one.

There is no way that you can create a career for someone without talent and no

way to stop a career of someone with talent." - Isaac Stern, violinist

Stern was sometimes accused of getting in the way of artists he didn't like. This was part of his response to that criticism. I think it's very likely that people can and do suppress careers for whatever reasons they may have - professional jealousy, vengeance, financial gain, personal differences.... It happened to Mozart and Zelenka, just to name two. The irony (sometimes) is that those artists who are "black-listed" can (with time) come back and surpass those who tried to stand in the way. If Stern was ever one of those who actually dampened someone's career, he won't suffer for it - he was too great an artist.

Friday, December 21, 2012

Napoleon quote

"I love power, but it is as an artist

that I love it. I love it as a musician

loves his violin, to draw out its sounds and chords and harmonies." Napoleon Bonaparte

It has been said that Napoleon once damaged a

cello (the Duport Stradivarius) by holding it in position with his stirrups –

while trying to play it. The cello was owned (for a long time) by cellist-conductor Mstislav Rostropovich. As far as I know, his heirs have not yet sold it. It is valued in the millions.

Labels:

cellos,

Duport Strad,

Napoleon,

Napoleon Bonaparte,

quotes,

Rostropovich,

violin quotes

Thursday, December 20, 2012

Jascha Heifetz quote

"I occasionally play works by contemporary composers and for two reasons: First, to discourage the composer from writing any more and, secondly, to remind myself how much I appreciate Beethoven." - Jascha Heifetz, violinist

"I occasionally play works by contemporary composers and for two reasons: First, to discourage the composer from writing any more and, secondly, to remind myself how much I appreciate Beethoven." - Jascha Heifetz, violinist

I'm pretty sure Heifetz said this half-jestingly. The serious half is what bothers me, although I might have said this myself.

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Artur Rodzinski quote

"Every violinist is a Misha or Sasha who has been built up by his

parents to be a Heifetz and sweep the world.

In the second fiddle section he has to play tremolo—ta-ta-ta. A soloist

never plays tremolo. How do I make them like the ta-ta-ta? By building their self-respect, by calling

them to my room, by endless talks…

[Hearing a great soloist] brings back their childhood memories of how

they planned to be soloists. Orchestral

work is maybe 75 percent psychology." Said to an interviewer by Artur Rodzinski, conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the Chicago Symphony.

"Every violinist is a Misha or Sasha who has been built up by his

parents to be a Heifetz and sweep the world.

In the second fiddle section he has to play tremolo—ta-ta-ta. A soloist

never plays tremolo. How do I make them like the ta-ta-ta? By building their self-respect, by calling

them to my room, by endless talks…

[Hearing a great soloist] brings back their childhood memories of how

they planned to be soloists. Orchestral

work is maybe 75 percent psychology." Said to an interviewer by Artur Rodzinski, conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the Chicago Symphony.

This quote pretty much sums up the view held by conductors and players alike. The Misha and the Sasha he mentions probably refers to Misha Elman and Sasha Jacobsen, just spelled a little differently. I'm guessing about that, of course.

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

Heimo Haitto

Heimo Haitto was a Finnish violinist, teacher, conductor, writer, and

actor born (in Viipuri, Finland) on May 22, 1925. He is Finland’s most famous violinist, although

he is now (unjustly) forgotten. Haitto was a

notorious, unconventional classical musician, in the style of Nicolo Paganini,

Arthur Hartman, Elias Breeskin, and Eugene Fodor. He was a gambler and loved drinking, although

it has been said he was not an alcoholic.

He deliberately turned his concertizing career off a couple of

times. For a time, he actually lived the

life of a vagabond, being literally homeless, traveling by train, in boxcars. However, notwithstanding all of the turmoil,

idiosyncrasies, romantic excesses, and bohemian lifestyle, he was a brilliant

violinist and a genuine artist. I think it can be said he had an extraordinary zest for life. YouTube

now contains some of his performances. As

Pinchas Zukerman has done, Haitto married a cellist (Beverly LeBeck, pupil of

Pablo Casals) and, later on, an actress (Marja-Liisa Nisula.) He married a third time in the mid 1970s. Haitto’s playing style reminds me somewhat of

Ivry Gitlis. Haitto wrote his memoirs in

the early 1970s (Heimo Haitto Maailmalla - published in 1976) but I don’t think there’s an English translation available. He also published a book on his violin playing experiences in 1994 - Viuluniakka Kulkurina. Although his father worked for the railroad,

he was also a violinist and gave Haitto his first lessons, beginning at age

5. At age 9, Haitto’s father took him to

the Vyborg Music Academy and left him entirely in the care of professor Boris

Sirpo (1893-1967.) (Vyborg and Viipuri

are one and the same city.) Under

Sirpo’s tough and rigid supervision, Haitto practiced almost constantly. At age 13, Haitto made his public debut in

Helsinki with the Helsinki Philharmonic and Sirpo on the podium. He also appeared in his first

movie – Soldier’s Bride – playing the part of a boy violinist. In that same year he won an international

violin competition sponsored by the British Council of Music in London and soon after briefly toured the Scandinavian

countries. In that year also, due to the

Russian-Finnish war, Sirpo brought Haitto to the U.S. to tour on behalf of the

Red Cross. In fact, Haitto's Guarnerius had been destroyed in an air raid. By then, Haitto had already been studying

rigorously under Sirpo’s very strict tutelage for five years. According to some sources, Haitto was not

allowed to have contact with his family during those years. Arriving in the U.S. in February of 1940, Haitto appeared with the

Philadelphia Orchestra in April of that year, playing the Paganini D major concerto. That was

his U.S. debut. He also soloed with many

other American orchestras. He played in

Carnegie Hall under John Barbirolli as well.

Eventually, accompanied by Sirpo, he settled in Portland, Oregon in

1942. Most European artists arriving in

the U.S in those years chose to begin their American careers from home bases in

New York, Philadelphia, Boston, or even Chicago, but not Haitto. In 1943, Haitto was released by his strict

teacher and set out on his own. He then settled

in Los Angeles. There, he played in the

Los Angeles Philharmonic (September/1952 to May/1954) and in Hollywood studio orchestras but appeared far

and wide as a soloist as well. He was 18

years old. He also appeared in another

movie: There is Magic in Music. That's the same movie that violinist Patricia Travers appeared in as a very young teenager. One

source says he enlisted in the military but another says he was not accepted

because he was foreign-born. In actuality, he desired to be a parachutist in the Marine Corps but his enlistment was declined, even though he had a letter of recommendation from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Instead, he was made a part of the Army Special Services. That's how he ended up in New York. Among the group that was in that Special Services Unit with Haitto were Ruggiero Ricci, Red Skelton, Mickey Rooney, and Eddie Fisher. In New York, he studied privately with Ivan Galamian, famous teacher at Juilliard. Haitto and Isaac Stern became friends there during this time - Stern was studying with Louis Persinger. With five other violinists, Haitto performed Paganini's 24 Caprices, each Caprice being alternately played by each violinist until all five played together at the end. Later, in Los Angeles, Haitto became friends with Jascha Heifetz and was a guest at Heifetz' house many times. Haitto had married Beverly LeBeck in New York in the spring of 1945. He

was 20 years old. His

new wife later (like him) became a cellist in the Los Angeles Philharmonic - 1949-1950 and, again, 1954-1955. Evidently, they did not play in the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the same time. Brilliant as he was, Haitto was dismissed

from the orchestra due to excessive absences and other problems. It has been reported that he loved to go to

Las Vegas and gambled heavily. During

the 1950s, he concertized and became the conductor of an orchestra in Salem,

Oregon. Haitto and Beverly moved to Seattle after Beverly left the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He eventually became the concertmaster of the Seattle Symphony and also conducted a youth orchestra at the Cornish School of Arts in Seattle. The third photo (circa 1955) shows Beverly and Haitto in the kitchen of the home of a close friend in Seattle. The photo is courtesy of Mr Ed Vainio, now a resident of Montana (USA), in whose parents' home the photo was taken. Haitto visited Finland in 1948 and again in 1956. He moved to Mexico City and

lived there (with Beverly LeBeck) between 1960 and 1962, serving as

concertmaster of an orchestra, but I don’t know which orchestra. At the time, there were four professional

orchestras in the city. In 1962, Beverly LeBeck began playing in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra (New York.) Haitto spent the years between 1963 and 1965 in Finland. After divorcing

LeBeck, he married Marja-Liisa Nisula (the actress) in 1964 but divorced her 2

years later. From 1965 to about 1976, he

was a vagabond (in the U.S.) and even spent some time in jail.

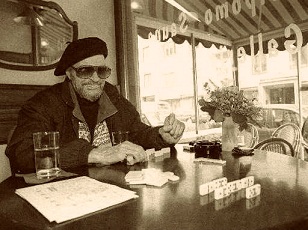

In 1976, Haitto returned to Finland permanently and began to practice again. He was 51 years old. He also remarried (Eva Vastari this time) in that year and, six months later, he was ready to play again. Vastari had been a journalist. In childhood he had played a Guarnerius violin but in adulthood I don’t know what he played. He actually built two (red) violins which he used for performances and recordings. Those violins now hang in Haitto's favorite restaurant in Helsinki - Tin Tin Tango. Vastari and Haitto

formed a duo. She read poetry and he

played. He also did some teaching and

lecturing at the Lahti Conservatory and other schools. They finally settled in

Marbella, Spain. The photo shows him

playing dominoes there. Haitto fell ill

in 1995 and died on June 10, 1999, at age 74.

Haitto made several commercial recordings which are still available, though they

are not easy to find; however, his recording of the Sibelius concerto (along with Six Humoresques which Sibelius wrote as Opus 87 and Opus 89) can be found here. Finlandia Classics has also released Haitto's recording of the Paganini concerto (number 1) and the Vieuxtemps concerto (number 4) - that release can be found here. He also recorded for Finnish National Radio (YLE) broadcasts - those recordings might not be available. You can hear his

unique style of playing here and here. Most of Heimo Haitto's video and audio files can be found on this Channel - it is Tuomas Haitto's YouTube channel - Tuomas Haitto is Heimo Haitto's nephew.

Sunday, December 2, 2012

Norman Carol

Norman Carol is an

American violinist and teacher born (in Philadelphia) on July 1, 1928. He is best known for being the Philadelphia

Orchestra’s concertmaster from 1966 to 1994.

Among orchestral musicians and concert artists around the world, his

name is instantly recognized. When musicians speak of concertmasters, Norman Carol is one of a small handful who immediately come to mind. He began

his violin studies at age 6 and made his first public appearance at age 9. At age 13, he entered the Curtis Institute

(Philadelphia) from which he graduated in 1947.

There, he studied with Efrem Zimbalist (one of Leopold Auer’s famous

pupils) and William Primrose, among others.

In that same year, Carol, then 18 or 19 years old, was invited (by

conductor Serge Koussevitsky) to join the Boston Symphony but Carol declined. He gave his Town Hall debut two years later –

April of 1949. He was 20 years old. The debut was very successful and was highly

praised. Interestingly, Carol then

joined the Boston Symphony (first violin section, but I don’t know at which

desk) and played in that orchestra from 1949 until 1952. Thereafter, he embarked on a solo career

which was soon interrupted by the Korean War.

After his military service, he restarted his solo career but was soon

tempted to join the New Orleans Symphony as concertmaster. He remained there between 1956 and 1959. In 1959, Carol became concertmaster of the

Minneapolis Symphony and stayed until 1965.

He and conductor Stanislaw Skrowaczewski began their tenures with the

Minneapolis Symphony in the same year.

In 1965, Eugene Ormandy chose Carol to lead the Philadelphia Orchestra

as concertmaster and his career there began in the 1966-1967 season. He was 39 years old. His first of dozens of appearances with the

orchestra took place on December 26, 1966.

However, he had already appeared as soloist with the orchestra back on March 12, 1954, during his brief concertizing career. On that occasion he played the Mendelssohn concerto. He played (in 1966) the Barber concerto, the same concerto which Albert

Spalding had premiered with the orchestra (with Ormandy on the podium) in 1941. Coincidentally, Carol was by then playing the

same violin Spalding had used for his premiere performance of this

concerto. [On November 13, 1954, Carol made his New York Philharmonic debut, playing Mozart's fifth concerto.] Carol stayed in Philadelphia

for 28 seasons. His retirement in 1994 was

mostly due to a shoulder injury he had sustained three years previously. Other violinists who have sustained injuries

which affected their careers are Rodolphe Kreutzer, Bronislaw Huberman, Jascha

Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, and Erick Friedman. It is likely that only concertmasters Richard

Burgin (Boston Symphony) and Raymond Gniewek (Metropolitan Opera Orchestra)

exceed his longevity with a single orchestra.

He may also have been the first to play the concertos of Benjamin

Britten, Paul Hindemith, and Carl Nielsen, as well as Leonard Bernstein’s

Serenade in Philadelphia. In 1979, Carol

began teaching at the Curtis Institute and is still teaching there. He has played a 1743 Guarnerius del Gesu since

about 1957. It had been previously owned

by Felix Slatkin, father of conductor Leonard Slatkin, and by Albert Spalding

before him. He has also owned a 1966 Sergio

Peresson violin and a 1695 Stradivarius previously owned (and played) by American

violinist Leonora Jackson and, before her, by Emil Mlynarski (one of the

founders of the Warsaw Philharmonic and father-in-law of pianist Artur

Rubinstein.) One of Norman Carol's recordings –

done for RCA in 1958 – is available here.

Norman Carol is an

American violinist and teacher born (in Philadelphia) on July 1, 1928. He is best known for being the Philadelphia

Orchestra’s concertmaster from 1966 to 1994.

Among orchestral musicians and concert artists around the world, his

name is instantly recognized. When musicians speak of concertmasters, Norman Carol is one of a small handful who immediately come to mind. He began

his violin studies at age 6 and made his first public appearance at age 9. At age 13, he entered the Curtis Institute

(Philadelphia) from which he graduated in 1947.

There, he studied with Efrem Zimbalist (one of Leopold Auer’s famous

pupils) and William Primrose, among others.

In that same year, Carol, then 18 or 19 years old, was invited (by

conductor Serge Koussevitsky) to join the Boston Symphony but Carol declined. He gave his Town Hall debut two years later –

April of 1949. He was 20 years old. The debut was very successful and was highly

praised. Interestingly, Carol then

joined the Boston Symphony (first violin section, but I don’t know at which

desk) and played in that orchestra from 1949 until 1952. Thereafter, he embarked on a solo career

which was soon interrupted by the Korean War.

After his military service, he restarted his solo career but was soon

tempted to join the New Orleans Symphony as concertmaster. He remained there between 1956 and 1959. In 1959, Carol became concertmaster of the

Minneapolis Symphony and stayed until 1965.

He and conductor Stanislaw Skrowaczewski began their tenures with the

Minneapolis Symphony in the same year.

In 1965, Eugene Ormandy chose Carol to lead the Philadelphia Orchestra

as concertmaster and his career there began in the 1966-1967 season. He was 39 years old. His first of dozens of appearances with the

orchestra took place on December 26, 1966.

However, he had already appeared as soloist with the orchestra back on March 12, 1954, during his brief concertizing career. On that occasion he played the Mendelssohn concerto. He played (in 1966) the Barber concerto, the same concerto which Albert

Spalding had premiered with the orchestra (with Ormandy on the podium) in 1941. Coincidentally, Carol was by then playing the

same violin Spalding had used for his premiere performance of this

concerto. [On November 13, 1954, Carol made his New York Philharmonic debut, playing Mozart's fifth concerto.] Carol stayed in Philadelphia

for 28 seasons. His retirement in 1994 was

mostly due to a shoulder injury he had sustained three years previously. Other violinists who have sustained injuries

which affected their careers are Rodolphe Kreutzer, Bronislaw Huberman, Jascha

Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, and Erick Friedman. It is likely that only concertmasters Richard

Burgin (Boston Symphony) and Raymond Gniewek (Metropolitan Opera Orchestra)

exceed his longevity with a single orchestra.

He may also have been the first to play the concertos of Benjamin

Britten, Paul Hindemith, and Carl Nielsen, as well as Leonard Bernstein’s

Serenade in Philadelphia. In 1979, Carol

began teaching at the Curtis Institute and is still teaching there. He has played a 1743 Guarnerius del Gesu since

about 1957. It had been previously owned

by Felix Slatkin, father of conductor Leonard Slatkin, and by Albert Spalding

before him. He has also owned a 1966 Sergio

Peresson violin and a 1695 Stradivarius previously owned (and played) by American

violinist Leonora Jackson and, before her, by Emil Mlynarski (one of the

founders of the Warsaw Philharmonic and father-in-law of pianist Artur

Rubinstein.) One of Norman Carol's recordings –

done for RCA in 1958 – is available here. Sunday, November 25, 2012

Sidney Weiss

Sidney Weiss is an American violinist, teacher, and conductor born (in

Chicago) on June 28, 1928. There is not too much information about him on the internet. He is best

known as one of the former concertmasters of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He is also known for making violins, although

I don’t know how many he has constructed.

I don’t know at what age he began studying but I do know he later

studied at the Chicago Musical College.

Later still he attended De Paul University (Chicago.) From 1956 to 1966 he played in the Cleveland

Orchestra – in the first violins but I don’t know how far up. He was 28 years old when he joined. George Szell was the conductor back then. From 1967 to 1972 he was concertmaster of the

Chicago Symphony. He then left for

Europe with his pianist wife and toured Europe with her as the Weiss Duo while

also serving as concertmaster of the Monte Carlo Philharmonic (the Orchestra of

the Monte Carlo Opera) between 1972 and 1978.

In 1979 he came to play with the Los Angeles Philharmonic as

concertmaster. He remained until his

abrupt departure in early May, 1994. He soloed with the orchestra on several occasions, one being April 15, 1981 (with the Sibelius concerto and Simon Rattle - before he became a very famous conductor - on the podium) and another on March 21, 1991 (featuring the Korngold concerto, Lawrence Foster conducting.) Among other

orchestras, he has conducted the Glendale Symphony (1997-2001) and participated in numerous

recording sessions in Los Angeles as well as undertaken tours as the violinist

with the Weiss Duo. You can find a few

of his recordings here. Sample sound

files are available here and here. One

of them is of the Mendelssohn concerto for violin and piano, a seldom heard

work. As far as I know, his best-known

pupil is Armen Anassian.

Sunday, November 18, 2012

Johann Stamitz

Johann Stamitz (Johann Wenzel Anton Stamitz) was a Czech violinist,

conductor, and composer born (in Deutschbrod, Bohemia) on June 18, 1717. He is remembered as the concertmaster of the

famous Mannheim Court Orchestra and father of two composers, Carl and

Anton. He has been called the “missing

link” between Bach and Haydn. Not too

much is known of his early life. In

1734, he attended the University of Prague but left after a year. He then traveled as a touring violin virtuoso

though little is known about where he went.

Then, in 1741 (or 1742) he was appointed to the Mannheim Orchestra. He was 24 years old. He soon became the concertmaster and leader

of the orchestra (1745), which he brought to a high degree of excellence, so

much so that it has been said that it was the finest in Europe. It was said in England that Stamitz’ orchestra

consisted of “an army of generals.” He

visited Paris in 1754 and performed (in September of 1754) at the Concerts

Spirituel, a well-known concert series which attracted much attention in those

days. He also put out some music through

French publishers. However, his music

was also published in England and the Netherlands. After returning to Mannheim in 1755, he died

two years later, on March 27, 1757. He

was barely 39 years old and Mozart was a one-year-old child. Stamitz is credited with having expanded the

role of wind instruments in symphonies as well as establishing the

four-movement form. These innovations

were later further developed by better-known composers such as Joseph Haydn,

Wolfgang Mozart, and Ludwig Beethoven.

Stamitz may have composed as many as 75 symphonies (the real number is

not known), 10 trios, 12 flute concertos, 2 harpsichord concertos, 14 violin

concertos, and a large amount of chamber music.

You can listen to one of his violin concertos here and one of his very

difficult trumpet concertos can be heard here.

Johann Stamitz (Johann Wenzel Anton Stamitz) was a Czech violinist,

conductor, and composer born (in Deutschbrod, Bohemia) on June 18, 1717. He is remembered as the concertmaster of the

famous Mannheim Court Orchestra and father of two composers, Carl and

Anton. He has been called the “missing

link” between Bach and Haydn. Not too

much is known of his early life. In

1734, he attended the University of Prague but left after a year. He then traveled as a touring violin virtuoso

though little is known about where he went.

Then, in 1741 (or 1742) he was appointed to the Mannheim Orchestra. He was 24 years old. He soon became the concertmaster and leader

of the orchestra (1745), which he brought to a high degree of excellence, so

much so that it has been said that it was the finest in Europe. It was said in England that Stamitz’ orchestra

consisted of “an army of generals.” He

visited Paris in 1754 and performed (in September of 1754) at the Concerts

Spirituel, a well-known concert series which attracted much attention in those

days. He also put out some music through

French publishers. However, his music

was also published in England and the Netherlands. After returning to Mannheim in 1755, he died

two years later, on March 27, 1757. He

was barely 39 years old and Mozart was a one-year-old child. Stamitz is credited with having expanded the

role of wind instruments in symphonies as well as establishing the

four-movement form. These innovations

were later further developed by better-known composers such as Joseph Haydn,

Wolfgang Mozart, and Ludwig Beethoven.

Stamitz may have composed as many as 75 symphonies (the real number is

not known), 10 trios, 12 flute concertos, 2 harpsichord concertos, 14 violin

concertos, and a large amount of chamber music.

You can listen to one of his violin concertos here and one of his very

difficult trumpet concertos can be heard here. Sunday, November 11, 2012

Lee Actor

Lee Actor is an American

violinist, composer, and conductor with an unfolding career as a very

successful composer, a career which almost happened as a second thought. He is also an electrical engineer and has

worked for years in the Information Technology field as well as the video game

industry. The dual endeavors are not as

far apart as many would imagine – not nearly.

Music and Science – especially mathematics – are intimately

intertwined. Actor’s engineering degrees

are from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (1970-1975, Troy, New York, about 150

miles north of New York City), one of the top science schools in the

country. Simultaneously studying music

and science, he chose to pursue science upon graduation and worked at GTE in

Boston for several years. One of his

violin professors was Angelo Frascarelli.

Although he began violin studies at age 7, kept up his pursuit of music

studies at Rensselaer, played violin and viola in the Albany (New York)

Symphony for three years (1972-1975), Actor also devoted time to composition. While working full-time, he studied

conducting privately with David Epstein at MIT (Boston, 1975-1978) and composition

with Donald Sur. Up until 1978, Actor

was playing violin in various orchestras on a regular basis and was composing chamber music works in his spare time. Three

years later (1979), he found himself in Silicon Valley (California), working in

the IT field but taking advanced courses in music as well.

While there, Actor secured his Master’s degree in composition from San

Jose State University (1982) and pursued further studies at the University of

California at Berkeley. In 1982, Actor

went to work for a start-up video game company. The industry was in its infancy. That led to his starting his own video game development company in 1988. In 1997, he was one of three founders of

Universal Digital Arts, a subsidiary of Universal Studios. Finally, in 2000, he went to work as Director

of Engineering for yet another high-tech start-up and retired from the industry one year

later. All this time, music had never been far

away. It is interesting that several famous musicians in history have had other careers, almost simultaneously

as they were playing or writing music – Jean-Marie Leclair, Charles Dancla,

Pierre Baillot, Alexander Borodin, Modest Mussorgsky, Ignace Paderewski,

Camille Saint Saens, Charles Ives, and Efrem Zimbalist come to mind. In 2001, Actor was invited to fill the

Assistant Conductor post with the Palo Alto Symphony. However, Actor had already been conducting

various orchestras since 1974. He was

later (2002) appointed Composer-in-Residence of the same orchestra and thus

began to compose prolifically. As far as

I know, Actor does not devote much time to small-scale works. Every review of his orchestral music

consistently praises his skills, originality, and ingenuity as a composer. Actor has mostly put the violin aside – as

have Alan Gilbert, Lorin Maazel, David Zinman, Jap Van Zweden, and a few other

violinists – in favor of other pursuits in music, composition and

conductng. English violinist Leonard

Salzedo used to play violin in the Royal Philharmonic (UK) and actually

continued playing in that orchestra for quite some time while devoting a lot of

his spare time to composition – mostly ballet music. That, however, is rare. Other violinists who turned from playing to

other endeavors include Theodore Thomas, Victor Young, Eddy Brown, Patricia

Travers, Iso Briselli, Pierre Monteux, Joseph Achron, Eugene Ormandy, and

Arthur Judson. Actor has composed

concertos for horn, alto saxophone, timpani, guitar, and violin, as well as

various orchestral works, including two symphonies, and most of his works have

already been recorded as well, by both European and American orchestras. It is an enviable record for someone “new” to

the composition scene, so to speak. A

typical comment from a critic reads: “[the work] is an incredible tour de

force, written by an immensely talented composer.” About his violin concerto, Pip Clarke (the

English violinist for whom it was written), says “The music is exciting,

passionate, and highly romantic,...filled with beautiful melodies and writing

throughout.” At a time when most music

schools here and abroad shun melody, structure, and tonality, Actor is a true

iconoclast. A video of his Horn Concerto

can be found here. As Bronislaw Huberman

always said, the true test of permanence in art has always been audience

acceptance and Lee Actor has tons of it to spare. It’s actually a very good thing that he

turned from violin playing to composition.

One of my next blogs will focus on his violin concerto.

Lee Actor is an American

violinist, composer, and conductor with an unfolding career as a very

successful composer, a career which almost happened as a second thought. He is also an electrical engineer and has

worked for years in the Information Technology field as well as the video game

industry. The dual endeavors are not as

far apart as many would imagine – not nearly.

Music and Science – especially mathematics – are intimately

intertwined. Actor’s engineering degrees

are from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (1970-1975, Troy, New York, about 150

miles north of New York City), one of the top science schools in the

country. Simultaneously studying music

and science, he chose to pursue science upon graduation and worked at GTE in

Boston for several years. One of his

violin professors was Angelo Frascarelli.

Although he began violin studies at age 7, kept up his pursuit of music

studies at Rensselaer, played violin and viola in the Albany (New York)

Symphony for three years (1972-1975), Actor also devoted time to composition. While working full-time, he studied

conducting privately with David Epstein at MIT (Boston, 1975-1978) and composition

with Donald Sur. Up until 1978, Actor

was playing violin in various orchestras on a regular basis and was composing chamber music works in his spare time. Three

years later (1979), he found himself in Silicon Valley (California), working in

the IT field but taking advanced courses in music as well.

While there, Actor secured his Master’s degree in composition from San

Jose State University (1982) and pursued further studies at the University of

California at Berkeley. In 1982, Actor

went to work for a start-up video game company. The industry was in its infancy. That led to his starting his own video game development company in 1988. In 1997, he was one of three founders of

Universal Digital Arts, a subsidiary of Universal Studios. Finally, in 2000, he went to work as Director

of Engineering for yet another high-tech start-up and retired from the industry one year

later. All this time, music had never been far

away. It is interesting that several famous musicians in history have had other careers, almost simultaneously

as they were playing or writing music – Jean-Marie Leclair, Charles Dancla,

Pierre Baillot, Alexander Borodin, Modest Mussorgsky, Ignace Paderewski,

Camille Saint Saens, Charles Ives, and Efrem Zimbalist come to mind. In 2001, Actor was invited to fill the

Assistant Conductor post with the Palo Alto Symphony. However, Actor had already been conducting

various orchestras since 1974. He was

later (2002) appointed Composer-in-Residence of the same orchestra and thus

began to compose prolifically. As far as

I know, Actor does not devote much time to small-scale works. Every review of his orchestral music

consistently praises his skills, originality, and ingenuity as a composer. Actor has mostly put the violin aside – as

have Alan Gilbert, Lorin Maazel, David Zinman, Jap Van Zweden, and a few other

violinists – in favor of other pursuits in music, composition and

conductng. English violinist Leonard

Salzedo used to play violin in the Royal Philharmonic (UK) and actually

continued playing in that orchestra for quite some time while devoting a lot of

his spare time to composition – mostly ballet music. That, however, is rare. Other violinists who turned from playing to

other endeavors include Theodore Thomas, Victor Young, Eddy Brown, Patricia

Travers, Iso Briselli, Pierre Monteux, Joseph Achron, Eugene Ormandy, and

Arthur Judson. Actor has composed

concertos for horn, alto saxophone, timpani, guitar, and violin, as well as

various orchestral works, including two symphonies, and most of his works have

already been recorded as well, by both European and American orchestras. It is an enviable record for someone “new” to

the composition scene, so to speak. A

typical comment from a critic reads: “[the work] is an incredible tour de

force, written by an immensely talented composer.” About his violin concerto, Pip Clarke (the

English violinist for whom it was written), says “The music is exciting,

passionate, and highly romantic,...filled with beautiful melodies and writing

throughout.” At a time when most music

schools here and abroad shun melody, structure, and tonality, Actor is a true

iconoclast. A video of his Horn Concerto

can be found here. As Bronislaw Huberman

always said, the true test of permanence in art has always been audience

acceptance and Lee Actor has tons of it to spare. It’s actually a very good thing that he

turned from violin playing to composition.

One of my next blogs will focus on his violin concerto. Sunday, October 21, 2012

Pip Clarke

Pip Clarke is a British

violinist and teacher who, although concertizing all over the world, has been living in the

U.S. since 1990. She is known for

playing in a very Romantic and expressive manner and is frequently compared to

legendary violinists Ruggiero Ricci, Jascha Heifetz, and Tossy Spivakovsky. Her tone has been described as haunting and

her style as breathtakingly romantic, though that description might be far too

limiting. She also has in her repertoire

a work which is a particular favorite of mine – the Bruch second concerto in d

minor, which is seldom played nowadays.

Clarke is also one of only two violinists I know of who does not have a

website – Silvia Marcovici is the other.

She has appeared with over 70 orchestras in the U.S. alone and has appeared

in recital in the most important venues in Canada, Asia, and Europe. Clarke began her music studies on the piano

at age 5 (in Manchester, England) and her violin studies (with Ruth Parker) two

years later. For six years she studied

with Roger Raphael at Chetham’s School of Music in Manchester, then with Lydia

Mordkovitch (pupil of David Oistrakh) at the Royal Northern College of Music

and later still with David Takeno at the Guildhall School of Music in London. Her public debut was at age 16 at the South

Bank Center in London. She embarked on

her very busy career upon graduation and has been concertizing ever since. Clarke also appeared on British television

with English composer and conductor Michael Tippett. Her American debut took place on October 27,

2007 at Carnegie Hall with the Korngold concerto. Although her repertoire encompasses all of

the standard concertos, she is especially lauded by critics for her

interpretations of Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy, and the Walton, Korngold,

Goldmark, and Dvorak violin concertos.

Reviewing a recent CD release, a well-known critic said: “She blazes

impetuously with plenty of dash and brio...she’s no mere purveyor of bland,

unruffled, unengaged precision.” Of her

first CD release, Musical Opinion (the oldest classical music journal in

England) wrote that it included “one of the most compelling accounts on record

of Chausson’s Poeme.” One of her most

recent recordings is of Lee Actor’s brilliant and unabashedly romantic violin

concerto, a work commissioned especially for her. You can listen to it here. As almost all concert artists now do today,

Clarke participates in music festivals far and wide, including the well-known

Ravinia Music Festival near Chicago.

Clarke also gives master classes in the U.S. and Europe. In recital and in recordings, her

accompanists have usually been pianists Sandra Rivers (accompanist of Sarah

Chang as well), Scott Holshouser, and (composer-pianist) Marcelo Cessena. Clarke has played violins by Joseph

Guarnerius and Matteo Goffriller, but her present violin is a modern (1983)

violin by Sergio Peresson. Other

musicians who own or have owned Peresson’s instruments include Yehudi Menuhin,

Pinchas Zukerman, Isaac Stern, Norman Carol, Jaime Laredo, Eugene Fodor, Ivan

Galamian, Mstislav Rostropovich, and Jaqueline du Pre. If you’ve been reading this blog for a while,

you might recall that Peresson was a Philadelphia violin maker (luthier) whose

instruments were in so much demand, he had to stop taking orders for violins in

1982. As far as I know, their sound is

indistinguishable from the very best Stradivarius or Guarnerius violins.

Sunday, October 14, 2012

Giuliano Carmignola

Giuliano Carmignola is an Italian violinist,

conductor, and teacher born (in Treviso, Italy) on July 7, 1951. He is known for his career as an eminent

exponent of Baroque music. However, his

repertoire encompasses works from the early Baroque to late modern. His repertoire includes the Schumann violin

concerto, a piece which has an interesting history. Nonetheless, his discography is focused on

the Baroque. He first studied with his

father. His later teachers included

Luigi Ferro, Nathan Milstein, Franco Gulli, and Henryk Szeryng. Among the music schools he attended are the Venice

Conservatory, the Accademia Chigiana (Siena, Italy – school of Salvatore

Accardo, John Williams, and Daniel Barenboim also) and the Geneva

Conservatory. From early in his career,

Carmignola has collaborated with many conductors, including Claudio Abbado, Roberto

Abbado, Trevor Pinnock, and Christopher Hogwood.

He has regularly played and recorded with various chamber orchestras –

the Virtuosi Di Roma (1970-1978), Mozart Orchestra, Il Giardino Armonico, Basel

Chamber Orchestra, Academy of Ancient Music, and Venice Baroque Orchestra are

among them. A similar path has been taken by Vladimir Spivakov and Fabio Biondi. Carmignola's best known recordings

are probably his complete Mozart concertos, complete Haydn concertos, a number of Pietro

Locatelli concertos, the Four Seasons (Vivaldi), and several two-violin

concertos by Vivaldi with Viktoria Mullova.

YouTube has many videos of his playing, including one of the Brahms

Double concerto. You can hear one such

video (of the Summer portion from the Four Seasons) here – it is played at the

fastest tempo I have ever heard. He

spends almost all of his time in Europe and did not make his U.S. debut until

2001 at the Mostly Mozart Festival in New York.

Since 2003, he has been an exclusive artist for the Deutsche Gramophone

label. Carmignola has taught at the

Advanced Music School in Lucerne (Switzerland) and at his old school, the Accademia Chigiana. His violins include the Baillot Stradivarius

of 1732 and a 1739 violin by Johannes Florenus Guidantus.

Sunday, October 7, 2012

Hubert Leonard

Hubert Leonard was a

Belgian violinist, teacher, and composer born (in Bellaire) on April 7,

1819. He is mostly remembered for having

taught – for almost 20 years - at the Brussels Conservatory where Charles De

Beriot, between 1843 and 1852, had also taught.

Leonard later settled in Paris where he continued to teach

privately. Among his most celebrated

students were Henry Schradieck and Martin Marsick. As a child, he began his studies with his

father and even gave a public concert before entering the Brussels Conservatory in 1832, at age

12. From age 9, he had also been

studying privately with an obscure teacher surnamed Rouma - this is probably one and the same as Francois Prume, another Belgian violinist who at age 17 (1832) was already professor of violin at the Liege Conservatory and who was only 3 years older than Leonard. Leonard enrolled in the Paris Conservatory in

1836 where his principal teacher was Francois Habeneck. He was 17 years old. Funding for his studies came from a wealthy

merchant. He left the conservatory in

1839 but stayed in Paris where he was employed by the orchestras of the Variety

Theatre and the Opera Comique. He toured

through various European cities from 1844 to 1848. A single source gives a different date for

this event in Leonard’s life (1845.) In

Leipzig, he met Mendelssohn who briefly tutored him in composition. Leonard also learned Mendelssohn’s concerto

and played it on tour. The concerto had

just then recently been premiered in 1845 by Ferdinand David but Leonard was

the first to play it in Berlin with Mendelssohn on the podium. Leonard began teaching at the Brussels

Conservatory in 1848 (Grove’s Dictionary says 1847), at age 29, but continued

to tour sporadically, extending his tours as far as Norway and Russia. After quitting the conservatory in Brussels

in 1866, he again settled in Paris, where he spent the next 24 years. Leonard’s compositions include five (or six)

violin concertos, duos for violin and piano, a cadenza for the Beethoven

concerto, fantasias, salon pieces, and etude books for violin, including a book

entitled 24 classic etudes. I am not

certain but I’m pretty sure the concertos have never been recorded. Supposedly, Leonard once said “The bow is the

master, the fingers of the left hand are but his servants.” Leonard died in Paris on May 6, 1890, at age

71. He had owned a G.B. Guadagnini (1751), an Andrea Guarneri (1665), and two Magginis, one of which went to his widow, who sold it in 1891.

Friday, October 5, 2012

Lorand Fenyves

Lorand Fenyves

was a Hungarian violinist and teacher born (in Budapest) on February 20,

1918. He is known for having spent much

of his career in Canada and is credited with helping establish an entire

generation of musicians in that country.

His teachers in Hungary included Jeno Hubay and Zoltan Kodaly,

internationally known violinist and composer, respectively. Though he made his professional debut at age

13, he graduated from the Franz Liszt Academy in 1934, at age 16. Two years later, having been recruited by

Bronislaw Huberman, he left Europe for Israel to become a founding member of

the Palestine Symphony (Israel Philharmonic.)

He soon became its concertmaster.

He was 18 years old. In 1940, he

helped found the Israel Conservatory and Academy of Music in Tel Aviv. He also organized the Israel String Quartet,

originally known as the Fenyves String Quartet.

He moved to Switzerland in 1957 (at age 39) where he was concertmaster

of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande and violin professor at the Geneva

Conservatory. He visited Canada in the

summer of 1963. The following year, he

accepted a one-year position at the University of Toronto. He actually remained there until his

retirement in 1983. In 2003, the

University gave a recital in honor of his 85th birthday – a common thing for

universities to do for their revered music professors. After his retirement from the University of

Toronto, Fenyves began teaching (in 1985) at the University of Western

Ontario. Nevertheless, he also gave

masterclasses at music centers around the world and performed as violin soloist

with well-known conductors and orchestras numerous times. You can listen to Fenyves play a Bach Sonata in

this YouTube audio file, recorded when he was about 70 years old. Among his pupils are Tasmin Little, Elissa

Lee, Scott St John, and Lynn Kuo.

Fenyves died (in Zurich, Switzerland) on March 23, 2004, at age 86. The 1720 (circa 1720) Stradivarius violin

which he owned – now known as the Fenyves Strad – was sold at auction in 2006

for about $1,500,000 USD. Fenyves had

purchased it in 1961.

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Lynn Kuo

Lynn Kuo is a

contemporary Canadian violinist, teacher, and lecturer with a very successful

and versatile career. In the orchestral

world, she is the Assistant Concertmaster of the orchestra of the National

Ballet of Canada. It is a prestigious

position. Not too many people know that

Joseph Joachim was assistant concertmaster in Leipzig under Felix Mendelssohn,

Zino Francescatti was assistant concertmaster with a French orchestra prior to

dedicating most of his career to touring, and Arnold Steinhardt (first

violinist of the Guarneri Quartet) was assistant concertmaster of the Cleveland

Orchestra. In the concert world, Kuo has

already toured Europe, including Austria, Hungary, Wales, Croatia, Serbia,

Romania, Bulgaria, and Ukraine, both in recital and with many major orchestras. As most concert violinists do, she also

performs with many chamber music ensembles and has frequently programmed the

works of several modern composers, whom she champions. She has also served as guest concertmaster of

Pinchas Zukerman’s orchestra, the National Arts Centre Orchestra, one of the

premier orchestras of Canada. Her music

studies began in her native St John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, at age

7. However, her first instrument was not

the violin – it was the piano. Among her

first teachers were Mark Latham, Nancy Dahn, and Eileen Kearns. Kuo later attended summer music festivals in

Aspen (Colorado), Kent-Blossom (Ohio, USA), Quebec, Banff, and Schleswig-Holstein

(in Northern Germany.) Her later

teachers in Toronto included Erika Raum, Mayumi Seiler, and Lorand Fenyves

(pupil of Jeno Hubay and one of the original members of the Israel

Philharmonic, having personally been invited by Bronislaw Huberman.) As do other contemporary violinists – Nigel

Kennedy, Itzhak Perlman, Alexander Markov, and Miranda Cuckson among them - Kuo

does not limit herself to purely classical music. Her collaborations with artists in other

genres are well-known. Many of Kuo’s performances

have been broadcast on radio and television as well, in Canada and

overseas. She has also been chosen to

present world premieres of several new works.

She has recorded for the NAXOS label and her new CD – simply titled LOVE:

Innocence, Passion, Obsession - is scheduled to be released soon. Critics have written that “her technique

appears flawless and her playing is dramatic, both rousing and melancholy.” You can hear for yourself here. She also has a Facebook page here where she

documents some of her career events - she recently received her DMA degree from

the University of Toronto. Kuo plays an

1888 Vincenzo Postiglione violin.

Lynn Kuo is a

contemporary Canadian violinist, teacher, and lecturer with a very successful

and versatile career. In the orchestral

world, she is the Assistant Concertmaster of the orchestra of the National

Ballet of Canada. It is a prestigious

position. Not too many people know that

Joseph Joachim was assistant concertmaster in Leipzig under Felix Mendelssohn,

Zino Francescatti was assistant concertmaster with a French orchestra prior to

dedicating most of his career to touring, and Arnold Steinhardt (first

violinist of the Guarneri Quartet) was assistant concertmaster of the Cleveland

Orchestra. In the concert world, Kuo has

already toured Europe, including Austria, Hungary, Wales, Croatia, Serbia,

Romania, Bulgaria, and Ukraine, both in recital and with many major orchestras. As most concert violinists do, she also

performs with many chamber music ensembles and has frequently programmed the

works of several modern composers, whom she champions. She has also served as guest concertmaster of

Pinchas Zukerman’s orchestra, the National Arts Centre Orchestra, one of the

premier orchestras of Canada. Her music

studies began in her native St John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, at age

7. However, her first instrument was not

the violin – it was the piano. Among her

first teachers were Mark Latham, Nancy Dahn, and Eileen Kearns. Kuo later attended summer music festivals in

Aspen (Colorado), Kent-Blossom (Ohio, USA), Quebec, Banff, and Schleswig-Holstein

(in Northern Germany.) Her later

teachers in Toronto included Erika Raum, Mayumi Seiler, and Lorand Fenyves

(pupil of Jeno Hubay and one of the original members of the Israel

Philharmonic, having personally been invited by Bronislaw Huberman.) As do other contemporary violinists – Nigel

Kennedy, Itzhak Perlman, Alexander Markov, and Miranda Cuckson among them - Kuo

does not limit herself to purely classical music. Her collaborations with artists in other

genres are well-known. Many of Kuo’s performances

have been broadcast on radio and television as well, in Canada and

overseas. She has also been chosen to

present world premieres of several new works.

She has recorded for the NAXOS label and her new CD – simply titled LOVE:

Innocence, Passion, Obsession - is scheduled to be released soon. Critics have written that “her technique

appears flawless and her playing is dramatic, both rousing and melancholy.” You can hear for yourself here. She also has a Facebook page here where she

documents some of her career events - she recently received her DMA degree from

the University of Toronto. Kuo plays an

1888 Vincenzo Postiglione violin. Sunday, September 16, 2012

Daniel Hope

Daniel Hope is a British

violinist, writer, teacher, and conductor, born (in Durban, South Africa) on

August 17, 1973. Besides his

concertizing, he is known for his varied interests and is also identified with

his extended promotion (more than 17 years) of the music of composers who

perished in concentration camps in World War II. Those composers include Gideon Klein, Pavel

Haas, Erwin Schulhoff, and Zigmund Schul.

As a violinist and advocate for various causes, he follows in the

footsteps of Bronislaw Huberman, Arthur Hartmann, Joseph Achron, Vladimir

Spivakov, Ivry Gitlis, and Shlomo Mintz. Hope began his violin studies at age four in England

as a result of his (indirect) close association with Yehudi Menuhin, whose

secretary was Hope’s mother. He later studied

at the Royal Academy of Music (London) with Zakhar Bron (teacher also of Maxim

Vengerov and Vadim Repin) until graduation.

However, by age 11, he was already playing concerts with Yehudi Menuhin,

with whom he collaborated artistically more than 60 times, including Menuhin’s

final concert on March 7, 1999 – Menuhin died five days later. At age 29, in the midst of an established

concertizing career, Hope joined the famous Beaux Arts Trio (Menahem Pressler

and Antonio Meneses) in 2002 and played with them until they disbanded (after a

53-year career) in 2008. Of course, he

has already played in most of the major concert halls with most of the major orchestras

in the world. He has for many years also

been engaged by some of the top music festivals. Hope has written a fascinating book entitled

Family Album but it is written in German – I don’t know whether an English

translation is available. His recording

catalog is not extensive but it includes the original version of the

Mendelssohn concerto. Thanks to this

recording, we can better appreciate Ferdinand David’s contribution in making

the concerto more Romantic in style – the original version sounds a little

archaic; in places, as if it had come from Viotti or Spohr. The recording is not available on YouTube but this one is - it's a more modern concerto. The New York Times has stated that Hope “puts classical works within a broader context – not just

among other styles and genres but amid history, literature, and drama – to

emphasize music’s role as a mirror for struggle and aspiration.” Among other violins, Hope has played a 1769

Gagliano (purchased from Menuhin) and a 1742 Guarnerius – the Lipinski

Guarnerius – on loan from a German family.

Monday, September 10, 2012

Orchestras in Trouble

The latest news about happenings

in the music industry includes plenty of articles regarding the financial

troubles the Minnesota Orchestra, the St Paul Chamber Orchestra, the Atlanta

Symphony, the San Antonio Symphony, and the Indianapolis Symphony (among

others) are experiencing. This comes on

the heels of bankruptcy declarations by the Philadelphia Orchestra, the

Syracuse Philharmonic, the Louisville Orchestra, the New Mexico Symphony, and

the Honolulu Symphony in 2011. The Detroit

Symphony musicians’ strike last year was also well-publicized. It’s like an epidemic. The situation is so dire that orchestra musicians

are not even being given the option to strike – the management is simply

locking them out of their working venues before any threats of strikes are

uttered by the musicians union – the American Federation of Musicians. That is truly unfair to the musicians. I won’t go into where you can find the

various sites where you can read detailed reports – they are in all the major

news journals. Just google orchestras in trouble and you’ll

find as many as you have time for. Many

professional experts (and other people “in the know”) have opinions as to what

might be to blame for the mess although, logically, there is really only one

culprit: the Board of Directors. The

union shares a little blame, but not much.

Among other things, the Board is responsible for fiscal oversight –

their function is not all that different from the function of any other

business board. Whatever else they do,

fiscal soundness is their most important responsibility. It is serious business, but it’s as simple as

running a household – you either live within your means or you don’t. It’s as simple as balancing an equation: X

(expenses) must equal Y (income.) X

cannot be greater than Y. Reading a

financial report is not rocket science.

Even I can do it. In any case, Boards

typically hire CPAs who take care of analyzing budgets for them. If an important and culturally significant

enterprise like a world-class orchestra goes under, the blame can only be laid

at the feet of the Board which has been appointed (or, in many cases,

volunteered) to make certain that these problems don’t suddenly catch up to

them. We are not talking about an ENRON

situation, where bankruptcy might be largely due to malfeasance, to put it

politely. We are talking about numbers on

a sheet of paper which send clear distress signals (warning bells, if you will)

far in advance of any peril. If an

orchestra suddenly finds itself in precarious circumstances, that can only mean

that the Board ignored the warnings which were visible to them. They failed to act. It cannot mean anything else. Commentators who are looking for other

answers – failures in planning, failures in marketing, failures in programing,

in audience building, in communications, in education outreach, in personnel

policies - are dancing around the real problem.

Arts organizations are not

expected to turn a profit. Since time

immemorial, artists – composers and performers alike - have turned to the

Church or to wealthy and generous patrons for assistance – Bach, Vivaldi, Wagner,

Prokofiev, etc. This is especially true

of orchestras because they are so expensive to maintain. There have been very few exceptions to the

need for subsidies (at some point) in any artist’s career, but only in the case

of individual artists. Today especially,

for instance, top violinists depend on benefactors to provide fine instruments

for them to use. If that’s not a

sudsidy, I don’t know what is. I have

never known any orchestra to subsist entirely on ticket sales. It could be done, but every ticket would have

to be priced in the stratosphere where, in fact, nobody could afford one. Not

only that, but every seat would have to be sold for every concert. If you look at it another way, the arts

patron – private or public – is really subsidizing the average concert goer, by

as much as 60% of the cost of attending any given concert. Without the benefactors, there would be no

art, except for the wealthy, as in days gone by. This formula however, does not absolve the

Board from its responsibility of looking after the fiscal health of the

orchestra. When funds are lacking, it

must sound the alarm, but never after the building has gone down in

flames. If the union – having received

due notice of impending doom - balks at renegotiating a contract which by its

weight may soon kill the whole enterprise, the union should be shut down because

at that point, it is getting in the way of sound fiscal planning. Nevertheless, it seems like that’s already a

moot point in the cases cited above.

Management

is frequently asked to enter into iron-clad contracts (containing salary

guarantees, etc.) which are unrealistic in income projections; they do so

hoping for best-case scenarios which usually don’t materialize. They also do so to avoid nasty confrontations

with the union. When these contracts

result in deficits, the Board then goes begging for extra funds to make up the

shortfall. Even wealthy Foundations and

patrons get tired of the same old routine and sometimes close their purse

strings; when that happens, a crisis results, especially in hard economic

times. Then, the finger pointing begins,

after which a seriously adversarial relationship between Management and

musicians develops. Usually, the

enterprise collapses and then is almost inevitably re-started under a cloud of

bad feelings. Contingency funds should therefore

always be in place to help during hard times and contracts should be written

with plenty of contigency clauses to cover unintended emergencies, regardless

of what the union demands. It beats

having to shut the doors. Will things

ever change? I doubt it. Ask the New York Philharmonic if it has a

surplus – or ask the Boston Symphony or the Chicago Symphony or the Cleveland

Orchestra. I hope so.

Thursday, September 6, 2012

Adolph Brodsky

Adolph Brodsky (Adolph Davidovich Brodsky) was a Russian violinist,

teacher, and conductor born (in Taganrog) on April 2, 1851. He is perhaps best known as the violinist who

premiered Tchaikovsky’s difficult violin concerto after Leopold Auer turned it

down because he found it unplayable.

Although he spent three years in the U.S., his career began and ended in

Europe. His grandfather and father (David)

were both violinists and he is said to have begun his lessons at age 4 in his

hometown. At age 9, he played a concert

in Odessa (Russia-Ukraine) and was subsequently sponsored by a wealthy patron,

to continue his studies in Vienna, at the Vienna Conservatory, with Joseph

Hellmesberger (the elder.) For a time,

Brodsky played second violin in the Hellmesberger Quartet, said to be the first

string quartet that actually bore a specific name. In addition, from 1866 to 1868, Brodsky

played in the Imperial (Vienna) Court Orchestra. He was 15 years old. In 1870, at about age 20, he left Vienna to

tour as a concert violinist. He settled

in Moscow in 1873 where he obtained a teaching position at the Moscow

Conservatory in 1875. He held this post

until 1878. On December 4, 1881, he

premiered the Tchaikovsky concerto in Vienna with Hans Richter conducting. He was 30 years old. Although initially dedicated to Leopold Auer,

the dedication was re-assigned to Brodsky.

Nevertheless, Auer subsequently learned the concerto and taught it to

his young pupils, one of which was Jascha Heifetz. Tchaikovsky was not present at Brodsky’s

premiere performance although he later attended a concert in Leipzig (in 1888)

in which Karl Halir was the soloist and was extremely pleased with the

concerto. From 1883 to 1891, Brodsky

taught at the Leipzig Conservatory. It

was here that Brodsky formed the Brodsky String Quartet with Ottokar Novacek,

Hans Sitt, and Leopold Grutzmacher. It

was also at Brodsky’s home that Tchaikovsky, Edvard Grieg, and Johannes Brahms

met (all at once) for the first time. Though

Brahms advised against it, in 1891, Brodsky accepted a position as

concertmaster of the New York Symphony (for which Carnegie Hall was built),

playing under Walter Damrosch. Brodsky

returned to Europe in 1894. Some sources

say he returned in 1895. He was 43 years

old. After spending some time in Berlin,

he was invited to England (by Charles Halle) to teach at the Royal Manchester

College of Music and to lead the Halle Orchestra as concertmaster. It was here that he changed his name from

Adolf to Adolph. From 1895 until his

death in 1929, Brodsky taught and was Director at the Royal College. He also occasionally conducted the Halle

Orchestra. It is said that he was one of

the first automobile owners in town. While

in Manchester, Brodsky re-established his string quartet with Rawdon Briggs,

Simon Speelman, and Carl Fuchs. In 1919,

Edward Elgar wrote and dedicated his Opus 83 string quartet (in e minor) to

this new Brodsky Quartet. In 1927,

Brodsky played the Elgar violin concerto with the Halle Orchestra with Elgar on

the podium. He was 75 years old. For 17 years (1880 to 1897) his violin was

the LaFont Guarnerius of 1735, for many years now played by Nigel Kennedy. Brodsky, who was also a chess player, died on

January 22, 1929, at age 77. Other than Naoum Blinder (Isaac Stern's teacher), I don’t

know if he had any famous pupils.

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

William Kroll

William Kroll was an American violinist, teacher, and composer born

(in New York) on January 30, 1901. As were violinists

Joseph Achron, Christian Sinding, Benjamin Goddard, Ottokar Novacek, and Arthur

Hartmann, he is famous for a single composition, Banjo and Fiddle, which most

concert violinists learn and play at one time or another. He began his violin studies with his father

(a violinist) at age 4. At age 9 or 10,

he went to Berlin to continue his studies with Henri Marteau, Joseph Joachim’s

successor at the Berlin Advanced School for Music. He returned to the U.S. after World War I

broke out in 1914. In New York, he

studied at Juilliard (Institute of Musical Arts) with Franz Kneisel from 1916

to 1921. He actually made his public

debut in New York at age 14. One source

describes his debut as “prodigious.” Although

Kroll concertized as a soloist in Europe and the Americas, he dedicated a great

deal of time to chamber music as a member of various chamber music ensembles,

well-known in their time: the Elshuco Trio (William Kroll, Willem Winneke, and

Aurelio Giorni, 1922-1929), the South Mountain Quartet (1923-), the Coolidge

Quartet (William Kroll, Nicolai Berezowsky, Nicolas Moldavan, and Victor

Gottlieb, 1936-1944), and the Kroll Quartet (William Kroll, Louis Graeler,

Nathan Gordon, and Avron Twerdowsky, 1944-1969.) The Coolidge Quartet was being paid $400.00

per concert in 1938, a good sum in those days – the equivalent of $6,550.00

today. From a very early age, he taught

at several music schools, namely Juilliard (1922-1938), Mannes College (1943-),

the Peabody Conservatory (1947-1965), the Cleveland Institute (1964-1967), and

Queens College (1969-) Kroll made very

few commercial recordings but an interesting one is a recording of three Mozart

Sonatas available here for about $120.00.

It includes the famous K454 sonata which Mozart wrote in 1784 for Regina

Strinasacchi, one of the very first female concert violinists. You can listen to a short Kroll recording on

YouTube here. Among his violins were a 1709

Stradivarius (the Ernst Strad, aka as the Lady Halle Strad, owned and played by

Heinrich Ernst, and, later, by Wilma Neruda) and a 1775 G.B. Guadagnini. Kroll died (in Boston) on March 10, 1980, at

age 79.

William Kroll was an American violinist, teacher, and composer born

(in New York) on January 30, 1901. As were violinists

Joseph Achron, Christian Sinding, Benjamin Goddard, Ottokar Novacek, and Arthur

Hartmann, he is famous for a single composition, Banjo and Fiddle, which most

concert violinists learn and play at one time or another. He began his violin studies with his father

(a violinist) at age 4. At age 9 or 10,

he went to Berlin to continue his studies with Henri Marteau, Joseph Joachim’s

successor at the Berlin Advanced School for Music. He returned to the U.S. after World War I

broke out in 1914. In New York, he

studied at Juilliard (Institute of Musical Arts) with Franz Kneisel from 1916

to 1921. He actually made his public

debut in New York at age 14. One source

describes his debut as “prodigious.” Although

Kroll concertized as a soloist in Europe and the Americas, he dedicated a great

deal of time to chamber music as a member of various chamber music ensembles,

well-known in their time: the Elshuco Trio (William Kroll, Willem Winneke, and

Aurelio Giorni, 1922-1929), the South Mountain Quartet (1923-), the Coolidge

Quartet (William Kroll, Nicolai Berezowsky, Nicolas Moldavan, and Victor

Gottlieb, 1936-1944), and the Kroll Quartet (William Kroll, Louis Graeler,

Nathan Gordon, and Avron Twerdowsky, 1944-1969.) The Coolidge Quartet was being paid $400.00

per concert in 1938, a good sum in those days – the equivalent of $6,550.00

today. From a very early age, he taught

at several music schools, namely Juilliard (1922-1938), Mannes College (1943-),

the Peabody Conservatory (1947-1965), the Cleveland Institute (1964-1967), and

Queens College (1969-) Kroll made very

few commercial recordings but an interesting one is a recording of three Mozart

Sonatas available here for about $120.00.

It includes the famous K454 sonata which Mozart wrote in 1784 for Regina

Strinasacchi, one of the very first female concert violinists. You can listen to a short Kroll recording on

YouTube here. Among his violins were a 1709

Stradivarius (the Ernst Strad, aka as the Lady Halle Strad, owned and played by

Heinrich Ernst, and, later, by Wilma Neruda) and a 1775 G.B. Guadagnini. Kroll died (in Boston) on March 10, 1980, at

age 79. Sunday, August 19, 2012

Mischa Mischakoff

Mischa Mischakoff was a

Russian (Ukrainian) violinist, teacher, and conductor born (in Proskurov, later known as Khmelnitzky)

on April 16, 1895. His year of birth is

also given as 1897. He is known for

having been concertmaster of many orchestras but especially the NBC Symphony

under Arturo Toscanini, the well-known and ill-tempered conductor. In fact, Mischakoff may well have been

concertmaster of more orchestras than any other violinist in history – ten that

I know of, not counting the St Petersburg Conservatory student orchestra. For the record, those include the St Petersburg Philharmonic (1913), the Bolshoi Ballet

(1920), the Warsaw Philharmonic (1921), the New York Symphony (1923), the

Philadelphia Orchestra (1927), the Chicago Symphony (1929), the NBC Symphony

(1937), the Chautauqua Symphony (during summer off seasons), the Detroit

Symphony (1952), and the Baltimore Symphony (1969.) He was a gifted artist who nonetheless

(unjustly) became less recognized as time went on. That is one of the disadvantages of playing

in an orchestra. However, even at age

75, Mischakoff was a phenomenal player.

You can hear for yourself here. As

a child, Mischakoff studied with Konstantin Konstantinovich Gorsky, an obscure

but highly accomplished Russian violinist.

At about age 10, he entered the St Petersburg Conservatory where he

studied under Leopold Auer’s assistant, Sergei Korguyev. He made his orchestral debut on June 25,

1911, playing the Tchaikovsky concerto.

He was either 14 or 16 years old.

Upon graduation (1912), he played very briefly in Germany (Berlin -

1912) and then became concertmaster in St Petersburg. Some sources have him playing in Moscow as

well – for the Moscow Philharmonic and the Moscow Grand Opera. He also served in a music regiment during

World War One – 1914 to 1918. He joined

the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra as concertmaster in 1920. He was 25 years old. In 1917, he supposedly gave the world

premiere of Prokofiev’s first concerto in Russia with Prokofiev conducting. His name should therefore be very closely

associated with the concerto but it isn’t.

A different source states that the world premiere was played in Paris on

October 18, 1923, followed three days later by the Russian premiere by Nathan

Milstein. The truth might be found in

one of Prokofiev’s diaries; unfortunately, I don't have access to them. In 1921, greatly assisted by Polish violinist and conductor Emil Mlynarski, he fled Russia (accompanied by cellist

Gregor Piatigorsky and, later, pianist Andre Kostelanetz) during a concert

tour which took them very close to the border with Poland - Nathan Milstein

too, later fled Russia while on a European tour with pianist Vladimir Horowitz